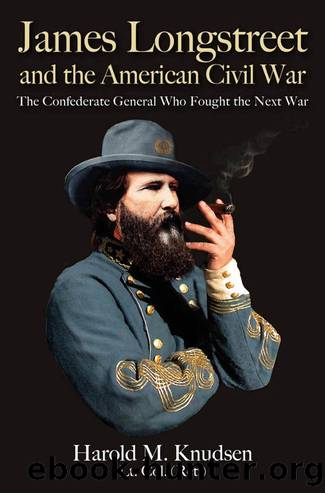

James Longstreet and the American Civil War by Harold M. Knudsen;

Author:Harold M. Knudsen;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC

Published: 2022-03-15T00:00:00+00:00

1 Fremantle, âDiary,â 338-340; Wert, Longstreet, 422-423. On July 7, 1863, McLaws confided in a letter to his wife: âI think the attack was unnecessary and the whole plan of battle a very bad one. Genl Longstreet is to blame for not reconnoitering the ground and for persisting in ordering the assault when his errors were discovered.â McLaws was mistaken, in that it was Leeâs plan and he had sent a captain to reconnoiter the area before telling Longstreet they would attack the Union Line. Longstreet tried to dissuade Lee from fighting at Gettysburg as well as attacking the Union Line. McLaws continued: âDuring the engagement he was very excited, giving contrary orders to everyone, and was exceedingly overbearing. I consider him a humbugâa man of small capacity, very obstinate, not at all chivalrous, exceedingly conceited, and totally selfish. If I can it is my intention to get away from his command.â McLaws was clearly upset about Longstreet not stopping the attack, leading part of his division in an attack, and having apparently been hard on him. However, McLaws was not among those who later claimed Longstreet had disobeyed Lee. McLaws supported Longstreet after the war. See Lafayette McLawsâs letter to wife, âA Series of Terrible Engagements,â in, The Civil War: The Third Year, ed. Brooks D. Simpson.

2 Freeman, R. E. Lee, 2: 317-349. As covered in earlier chapters, the close relationship between Lee and Longstreet began within a few days of meeting each other after Lee took over from Johnston. Longstreet became his co-planner, Lee stayed with Longstreet, and it is also evident they got along well personally. Lee recognized Longstreetâs long, consistent service, and infantry expertise. In theory, it is possible that in 1861 Lee was dissatisfied with his early performance in West Virginia, and once he had army-level command he overcompensated with aggressiveness as he went through a period of late-career education, learning the true capabilities of the combat arms branches in 1862 and 1863. Aggressiveness brought success, but at a high cost. Malvern Hill, for example, shows where the aggressiveness went too far, and perhaps Lee then sought the infantry expertise of Longstreet at Second Manassas. At Antietam and Gettysburg he listened but ultimately went with his own judgments.

3 For information on Leeâs prewar military career, consult Margaret Sanborn, Robert E. Lee: A Portrait 1807-1861, (New York: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1966), 237-317.

4 Freeman, R.E. Lee, 1: 360-418. Freeman was critical of Longstreet in his 1930s four-volume biography, regarding this role. It must be noted that Freeman was not a soldier and had no career understanding of Army branch professional development and how a career path determines an officerâs suitability for high-level combat arms command positions. Freeman assumed Lee was proficient in combat arms branch tactics at a level equal to or greater than those who were combat arms officers. This is a fallacy, perhaps proven at least in two major battles: his failed and costly attack against a defense-in-depth at Malvern Hill, and at Gettysburg.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| United States | Abolition |

| Campaigns & Battlefields | Confederacy |

| Naval Operations | Regimental Histories |

| Women |

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(2702)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2459)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(1971)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(1857)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(1752)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(1729)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(1671)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1632)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1622)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(1612)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1530)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(1519)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1425)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1347)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1346)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1346)

Decision Points by George W. Bush(1261)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1247)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1231)